the racist history of school choice

separate but equal - Brown v. Board of Education (1954)

Brown v. Board of Education NGP, Topeka Unit - White and Colored Signs - Ser Amantio di Nicolao, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

A signed letter from senators & representatives from the south, in retaliation for brown v. board of education

We regard the decision of the Supreme Court in the school cases as a clear abuse of judicial power. It climaxes a trend in the Federal judiciary undertaking to legislate, in derogation of the authority of Congress, and to encroach upon the reserved rights of the States and the people. The original Constitution does not mention education. Neither does the 14th amendment nor any other amendment. The debates preceding the submission of the 14th amendment clearly show that there was no intent that it should affect the systems of education maintained by the States.

The very Congress which proposed the amendment subsequently provided for segregated schools in the District of Columbia. When the amendment was adopted, in 1868, there were 37 States of the Union. Every one of the 26 States that had any substantial racial differences among its people either approved the operation of segregated schools already in existence or subsequently established such schools by action of the same lawmaking body which considered the 14th amendment.

Though there has been no constitutional amendment or act of Congress changing this established legal principle almost a century old, the Supreme Court of the United States, with no legal basis for such action, undertook to exercise their naked judicial power and substituted their personal political and social ideas for the established law of the land.

This unwarranted exercise of power by the Court, contrary to the Constitution, is creating chaos and confusion in the States principally affected. It is destroying the amicable relations between the white and Negro races that have been created through 90 years of patient effort by the good people of both races. It has planted hatred and suspicion where there has been heretofore friendship and understanding.

With the gravest concern for the explosive and dangerous condition created by this decision and inflamed by outside meddlers: We reaffirm our reliance on the Constitution as the fundamental law of the land. We decry the Supreme Court's encroachments on rights reserved to the States and to the people, contrary to established law and to the Constitution. We commend the motives of those States which have declared the intention to resist forced integration by any lawful means. .

We pledge ourselves to use all lawful means to bring about a reversal of this decision which is contrary to the Constitution and to prevent the use of force in its implementation.

segregation academies and runyon v. mccrary (1976)

How Leaders of the Religious Right sanitized segregation to lure in Christian voters

E.L. Malvaney from Jackson, MS, United States, CC BY-SA 2.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

Removing Tax-Exempt Status from segregation academies

“Charitable” educational institutions

Paul Weyrich and the Moral Majority

Lynchburg Christian School and Bob Jones University Refused to integrate

How Christians used the Bible to Justify Segregation

The Curse of Ham

Africans must be Christianized

George Kendall Warren, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

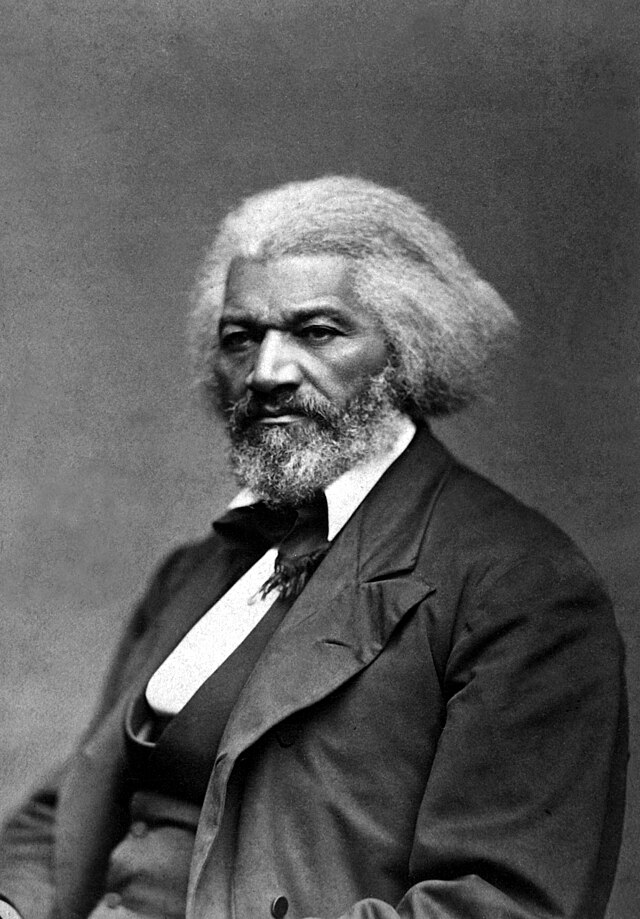

Frederick Douglass

trump lifted ban on segregated facilities because of "DEI"

The Trump administration recently changed federal regulations, no longer explicitly prohibiting contractors from maintaining segregated facilities like restaurants, waiting rooms, and drinking fountains. This shift follows President Trump's executive orders on diversity, equity, and inclusion, which repealed a 1965 order by President Lyndon B. Johnson requiring contractors to uphold civil rights laws. The change, which affects the Federal Acquisition Regulation (FAR), is seen as symbolic but significant in its potential impact on workplace integration. Despite these changes, businesses must still comply with federal and state laws, including the Civil Rights Act of 1964. The modification was implemented quickly, bypassing the usual public comment period, which raised concerns about the process's transparency. The General Services Administration has stated that the changes align with current executive orders.