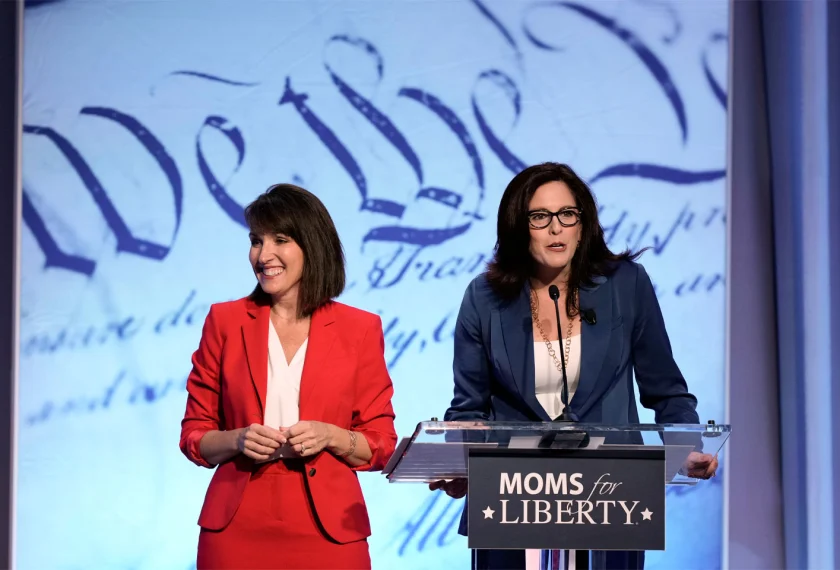

The Original Moms for Liberty

The World War II isolationist movement in the United States was marked by a strong sentiment among various groups, including religious organizations, advocating for non-involvement in the escalating global conflict. Despite being aware of the Holocaust and the atrocities committed against Jews in Europe, many churches and conservative factions sought to convince Americans that staying out of the war was paramount to preserving national interests. Notable among these groups were the America First Committee and the Mother's Movement, which argued that involvement in the war would lead to unnecessary sacrifices. Today, echoes of this isolationist rhetoric can be seen in contemporary organizations like Moms for Liberty, which controversially includes quotes from Hitler in their newsletters, drawing unsettling parallels between past and present ideologies regarding governance and civic responsibility.

Elizabeth Dilling and The Red Network-A Who’s Who and Handbook of Radicalism for Patriots

This book cataloged more than 1300 “Reds” and their affiliations, including Jane Addams, Albert Einstein, Sigmund Freud, Mahatma Gandhi, Senator Robert M LaFollette, and Eleanor and Franklin Roosevelt, The book went into eight printings and sold more than 16,000 copies by 1941. Organizations such as the KKK, and the German-American Bund gave away thousands more

She also published a book called The Plot Against Christianity, later republished as The Jewish Religion: Its Influence Today.

Dilling was a prominent member of the pro-fascist extreme right in the United States during the 1930s and 1940s. According to professor Glen Jeansonne, who studied Dilling and her allies, she considered herself a “professional patriot,” defending flag and faith against an array of threats that included Jews, communism, the New Deal, and the liberal Democrats who supported New Deal policies.

Elizabeth Dilling's Trip to Russia and Communism

She found her passion as a political activist of the Red-baiting variety on a month-long tour of the Soviet Union with her husband Albert in 1931. She came back an avid anticommunist—a position that would be absolutely understandable if it hadn’t developed into being “anti” a lot of other things. Over time, her hatred for communism grew into sympathy for the fascism of Hitler and Mussolini, which she saw as a bulwark against Soviet Russia. A Nazi newspaper gave her the nickname “the female Führer.” She was one of the most outspoken critics of FDR’s New Deal, which she referred to as the “Jew Deal”.

She was involved in an attempt, led by retailer Charles Walgreen (yes, like the pharmacy), to close her former alma mater*** the University of Chicago as a communist institution. Henry Ford (yes, the automobile manufacturer), who was against all the things she was against and willing to put his money where his hatred was, hired her to investigate communism at the University of Michigan. (She also investigated UCLA, Cornell, and Northwestern—finding all of them to be hotbeds of communism and a menace to the youth who studied there.)

She also expressed sympathy for Nazi Germany.

Isolationism and the Mother's Movement

The Mother's Movement

The America First Committee

In an article from July 11, 2016, The Heritage Foundation praises the America First Committee, stating that “Although the term “America First” has been resurrected in the 2016 presidential campaign, its historical origins have been buried under years of American politics and sketchy history. The America First movement has been described as isolationist, anti-interventionist, anti-Semitic, xenophobic, and a bunch of know-nothings. That narrative fails on several levels.”

Despite Heritage Foundation’s attempt to make America First sound reasonable, even republican leaders like Mitch McConnell hear echoes of Pre-World War II isolationism.

In his Lexington comments, [McConnell] said the world faces a situation as dangerous as the period before World War II and made a comparison that cast a frequently-used Trump campaign slogan in a negative light

"Now there are some who argue why bother doing any of this?" he said, referring to foreign aid. "Reminds me of the 30s slogan back then. (It) may sound familiar to you. It was called America First."

Isolationism and the Holocaust

Democracy and Anti-Semitism

You can see a shift in the tone of the Heritage Foundation’s tone throughout the years. An article from the Heritage Foundation on January 24, 2005 titled “Democracy and Anti-Semitism” describes isolationism through the apathy of powerful religious leaders turning a blind eye to Hitler’s atrocities:

“In his harrowing memoir of survival, Night, Elie Wiesel asks: "How could it be possible for them to burn people, children, and for the world to keep silent?"

There can be only partial answers to that question, but certain facts surely contributed to the silence, especially in the United States. Throughout the 1930s, most Americans wanted nothing to do with another European war. Despite mounting evidence of Hitler's barbarism -- and his ultimate military aims -- the mood was stubbornly isolationist. This was particularly true of the nation's religious leaders, who were preoccupied with America's economic and social injustices.

Some saw German aggression as a kind of divine judgment.

Christians were Complicit in Preventing American Intervention

The Christian Century magazine, the nation's leading religious journal, devoted itself to opposing U.S. intervention.

These "progressive" religious thinkers preserved their political and moral neutrality only by downplaying Hitler's anti-Semitic rage.

They knew better. The arrests, deportations, and imprisonment of Jews across the continent were widely reported in the American press. Yet the nation's Christian leadership failed even to lobby for immigration reform to absorb more refugees. No wonder: From 1933 to 1941, more than 100 anti-Semitic groups appeared in the United States, many with a Christian hue.

There were other voices. Protestant theologian Reinhold Niebuhr led a group of "Christian realists" who insisted that Hitler be judged not only by his military ambitions, but by the ruthlessness of his anti-Semitism. They accused the isolationists of misusing Christian ethics in order to "drug their conscience" toward Nazi atrocities. "The Christian ideal of love," Niebuhr warned, "has degenerated into a lovelessness which cuts itself off from a sorrowing and suffering world."

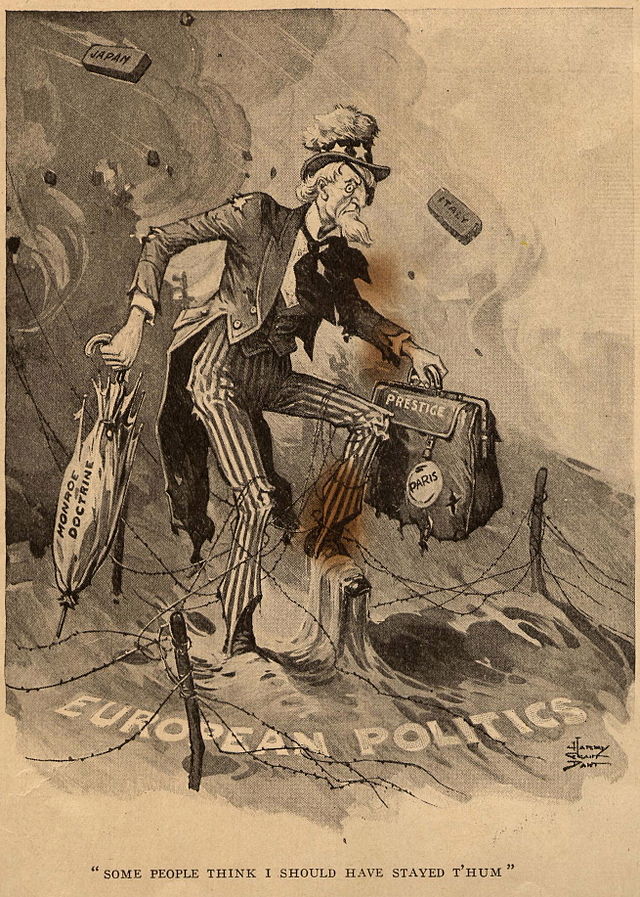

Harry Grant Dart, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

At the heart of the realist case for U.S. intervention was a biblical view of human evil and the political duty to restrain it. Reluctance to render ultimate judgments of Nazism, they argued, guaranteed the triumph of a racist ideology and the enslavement or death of millions. "It is important that Christianity should recognize that all historic struggles are struggles between sinful men and not between the righteous and the sinners," Niebuhr wrote after the fall of France. "But it is just as important to save what relative decency and justice the western world still has, against the most demonic tyranny of history."

The temptation to forget that difficult lesson is still with us. It’s worth remembering that the Jews were not rescued from Hitler's death camps by obsessing over the failings of free nations. Now, as then, imperfect democracies are called upon to combat anti-Semitism and all ideologies of hate—because they are the only democracies available for the job.

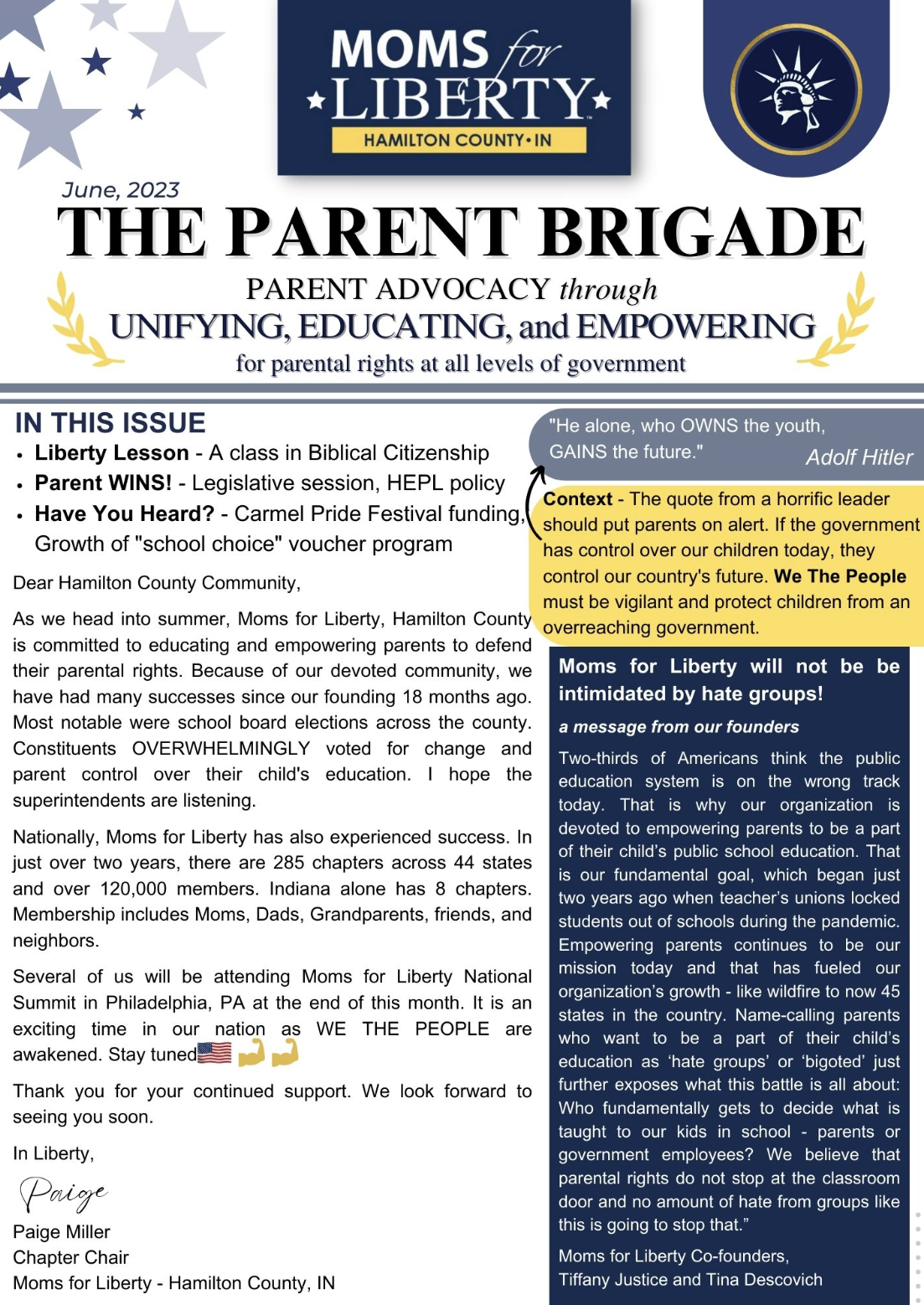

The Heritage Foundation Defends Moms for Liberty using a Hitler Quote in their Newsletter

Communism a greater threat than Antisemitism

"He who OWNS the youth, GAINS the future."